Noobmasterplayer123

The Practice Problem

The Practice Problem

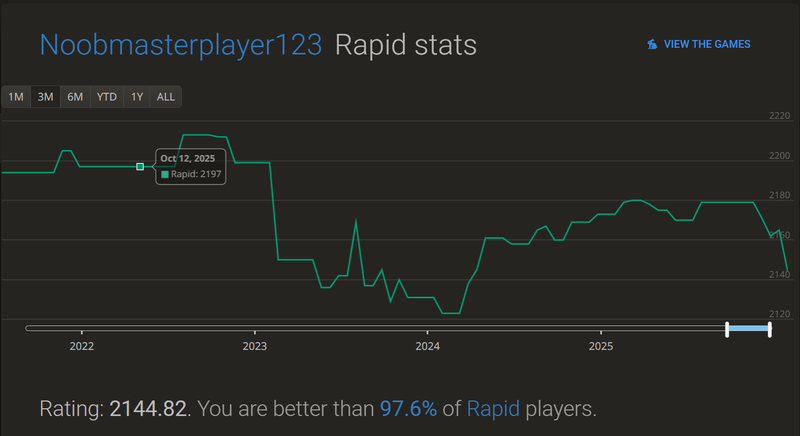

I used to think I had this chess improvement thing figured out. At 2200 rapid on Lichess, I could navigate the opening labyrinth reasonably well, and I'd studied enough endgames to know what I was supposed to do. My repertoire was solid. I could explain the key ideas of my openings and rattle off the critical endgame techniques.

Then I'd sit down to play, and somewhere around move 15, I'd drift. Not because I didn't know the theory, I did. But when it came time to actually execute, to find that first independent move or convert a winning endgame, I'd hesitate. I'd second-guess myself. And slowly, game by game, I watched my rating slide from 2200 to 2150.

The frustrating part wasn't the losses themselves. I knew that I understood these positions intellectually, but couldn't translate that understanding into good moves over the board. I knew the Lucena position. I knew when to trade pieces in the French. However, I've learned that knowing and doing are entirely different skills.

(My Rapid rating graph, I have dropped a lot of points)

The Gap Between Knowledge and Execution

After dropping those 50 rating points, I started analyzing my losses more carefully. The pattern was clear: I wasn't losing because I didn't know the theory. I was losing because I'd never actually practiced applying that theory under realistic conditions.

Think about how we typically study chess. We read books, watch videos, and play through master games. Maybe we can use an opening trainer to memorize moves. All of this is valuable, but it's fundamentally passive. You're absorbing information, not developing the instincts and pattern recognition that come from actually playing the positions repeatedly.

When you reach that critical position in a real game, the one where theory ends and you're on your own, you need more than intellectual understanding. You need the confidence that comes from having been there before, from having played this position enough times to feel what's right. In the game, I totally forgot that Bd3 is not a great move, as I started seeing ghosts, even though I thought theoretically I knew what I was doing, it turns out it wasn't the move that works practically.

What's Out There (and What's Missing)

I looked at the existing options for addressing this. Lichess lets you play against Stockfish at various strength levels, which is useful, but the engine's play feels distinctly inhuman even at lower depths. The moves are too perfect, the style too mechanical. It's not like facing a 2000-rated human.

Chess.com has personality bots that try to mimic human play, but in my experience, they're inconsistent. Sometimes they blunder in ways no real player would; other times they suddenly play computer moves in openings or endgames that feel nothing like what you'd face at that rating level.

There are other platforms out there that tackle this problem in different ways, and if those work for you, that's great. For me, I needed something specific: a way to repeatedly practice the exact positions where I was struggling, against opponents that felt like the players I actually face at my rating level.

(Stockfish 6 plays this weird-looking opening and feels to the engine like, when I face players at 2100 rapid, I face open Sicilian a lot)

(Stockfish 6 plays this weird-looking opening and feels to the engine like, when I face players at 2100 rapid, I face open Sicilian a lot)

My Solution: ChessAgine Play Bot Page

So I built something for myself. Not because I think everyone needs this particular tool, different players have different needs and preferences, but because this is what I needed to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

The core concept is simple: load a position, play it against an opponent that mimics human play at a realistic rating level, review what happened, then play it again. And again. Deliberate practice of specific positions until they stop being abstract theory and start being instinctive understanding.

What makes this work for me is the integration of Maia chess engines at different rating levels (1100-1900) and access to rating-filtered opening books from Lichess. When you practice an opening position against Maia 1800, you're not facing computer moves; you're facing the kinds of moves a 1800-rated human would actually play, including the slightly inaccurate ones. The opening responses come from actual games at that rating level.

For practice at my level and above, I can switch to Leela Chess Zero or Elite Leela, which play at roughly 2500+ strength with master-level opening knowledge. And when I want to see the absolute best moves, Stockfish 17.1 is there for computer-perfect analysis.

(Play bot page has the ability to change sparring bots based on your ELO, can select time control, and sparring position)

(Play bot page has the ability to change sparring bots based on your ELO, can select time control, and sparring position)

Here's what changed for me: I stopped trying to memorize my way through chess and started playing positions until they made sense.

Let's say I kept mishandling the transition in the French after 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nd2. I'd load the position after move 10, right where I usually started drifting, and play it out against Maia 1900 or Leela. I'd make some mistakes, try different ideas, and see how the position developed.

After the game, I'd review exactly where I went wrong. Then I'd play the same position again. Same starting point, but the game would unfold differently. Chess is complex enough that even from identical positions, you face different challenges each time.

After five or six games from that position in a single session, something shifts. You start recognizing the patterns. You feel which pawn breaks work and which don't. You develop intuition about when to trade and when to keep tension. It stops being about remembering and becomes about understanding.

(Practicing the French lines against Maia 1900 bot, the theory from black comes from Lichess opening explorer at the 1900 - 2000 level)

(Practicing the French lines against Maia 1900 bot, the theory from black comes from Lichess opening explorer at the 1900 - 2000 level)

The Endgame Problem Is Worse

At least with openings, you play them somewhat regularly. But specific endgames? At my rating, I might reach a particular rook endgame once every thirty or forty games. How are you supposed to master something you seldom practice?

I used to study endgames by reading Dvoretsky and working through Silman. I understood the concepts: activate the king, cut off the opponent's king, and build a bridge in the Lucena position. But understanding intellectually and executing with the clock ticking are very different things.

With the play bot, I can practice the same endgame five times in twenty minutes. The first attempt, I might botch the technique. The second time, I remember the idea but executed it inefficiently. By the third or fourth repetition, it's starting to flow naturally. By the fifth time, it's becoming automatic.

That repetition is what actually embeds the knowledge. Not reading about it, not memorizing it, playing it until your hands know what to do.

(Practicing the Lucena position in a rapid game against Maia2 1900-rated bot)

(Practicing the Lucena position in a rapid game against Maia2 1900-rated bot)

The Training Loop

The way I use this now: I identify positions where I'm consistently underperforming. Maybe I reviewed my recent games and noticed I keep misplaying a certain French structure. Or I realized I'm losing drawn rook endgames because I panic in the conversion.

I load that position and play it against an opponent at or slightly above my level, usually Maia 2000 or Leela. I play it completely, even if I'm losing, because sometimes the practice is in managing the resulting difficult position.

After each game, I study the review. Where did I leave the known theory? Where were the critical mistakes? What should I have played instead?

Then I play it again immediately. You'd be surprised how much you absorb even from one game. Your moves become more purposeful. You avoid some previous mistakes and make new ones, which is fine; that's how you learn the full landscape of the position.

I do this five to ten times in a session, a few times a week, with different positions. Within a month of starting this approach, I noticed a real difference. Those post-opening transitions became less daunting. Endgames felt manageable instead of like walking through a minefield.

(Reviewing the game in the analysis game tab is as important as playing against Maia multiple times to get the practice.)

(Reviewing the game in the analysis game tab is as important as playing against Maia multiple times to get the practice.)

Not a Magic Solution, Just a Tool

I still do tactics puzzles. I still analyze my games with engines. I still watch instructional content. This isn't about replacing everything else; it's about adding a specific type of practice that I was missing.

For me, position sparring has become the most efficient way to convert theoretical knowledge into practical skill. It's not that puzzles or full games don't have value, they absolutely do. But when I need to master a specific position, when I need to turn "I know what I'm supposed to do here" into "I can actually do it," this is what works.

Maybe you already have a training method that accomplishes the same thing. Or maybe, like me, you've been looking for a way to practice that feels more realistic than puzzles but more focused than full games. If you're interested, ChessAgine is my attempt at solving that problem (Note chessAgine is Free Open Source Software FOSS). It might work for you, or it might not. But if you're dropping rating points because you can't execute what you know, it might be worth trying a different approach to practice.

After all, at a certain level, we all know roughly what we should be doing. The question is whether we've practiced it enough to actually do it when it matters.

Thanks for reading,

Noob

You may also like

thibault

thibaultHow I started building Lichess

I get this question sometimes. How did you decide to make a chess server? The truth is, I didn't. Noobmasterplayer123

Noobmasterplayer123ChessAgine Neural Net Integration

I go over how I integrated popular Neural Nets in ChessAgine CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… HollowLeaf

HollowLeaf