Do this on your opponent's turn

5 simple habits to use your time better and level up your chessMost chess players throw away half their thinking time.

Not on their move, but on the opponent’s.

You stare, you zone out, you get up and walk around.

Once they play their move, you scramble back. You burn time just to work out what changed, you play your move and switch off again.

It’s a negative loop, and it’s costing you games.

In this post I’ll give you five practical habits you can use on your opponent’s turn in your next game, drawn from my experience as an International Master and coach.

I’ve also included insights from three grandmasters I talked to.

If you’re looking for little-known habits that level-up your chess, steal these today.

Habit #1: Think about your opponent’s strongest move.

When it’s your turn, you naturally look for the best move for you. That’s what most of your training is for.

The difference between masters and amateurs shows up on the opponent’s turn, because amateurs often use that time to daydream about the move they hope gets played.

Masters save time by predicting. They look for the opponent’s strongest move in advance, both while choosing their own move and during the opponent’s turn.

They’re constantly asking this question:

“If I were them, what’s the best way to make my life miserable?”

By thinking about the best moves for both sides, you understand the position deeper.

And you save time because when the opponent plays a strong move, you aren’t surprised.

- You’ve already thought about why they want to play that, as well as

- What your best response might be.

Amateur players, on the other hand, often stay in their comfort zone by only looking at moves by the opponent that let you continue with your plan.

When your opponent plays a strong move, it’s a surprise and you need to start thinking from scratch, panicking and burning more time.

So how do you build this habit of looking for the opponent’s strongest move?

A good starting point is asking yourself what move you least want them to play. The move that you feel uncomfortable thinking about, or one you don’t know what to do against.

At the start, looking at these moves and having to think hard isn’t going to be fun. But when you notice that this habit helps you in your games, it’ll become something you enjoy.

It becomes more automatic as you get better, and you get better because looking for your opponent’s strongest move becomes more automatic.

And here’s proof this matters at the very top: Australian grandmaster and legend, Ian Rogers told me a story about Anand.

When Anand was 15 or 16, he was playing classical games at an incredible pace. He would barely use any time on the clock, and Ian saw this in person. His conclusion was that Anand’s time advantage came from using the opponent’s time to do the real work, predicting moves and calculating the key lines. So when it was his turn, he was basically just double-checking.

This shows a glimpse of how far you can take this skill, or art, of thinking on the opponent’s turn.

Habit #2: Think about the plans for both sides.

The problem with locking in and calculating a lot on your opponent’s turn is that you don’t know what they’re going to play. Most of the lines you look at might be wasted if they play another move you didn’t even look at. And from calculating intensely, you can tire yourself out.

So when it’s your opponent’s move, zoom out and think about the bigger picture.

Taiwanese grandmaster and coach, Raymond Song told me he thinks about these 5 things:

- Which is my worst-placed piece?

- How should I improve it?

- Where do my pieces belong?

- How is my opponent likely to manoeuvre their pieces?

- What are the potential pawn breaks for both sides and what are the resulting positions going to look like?

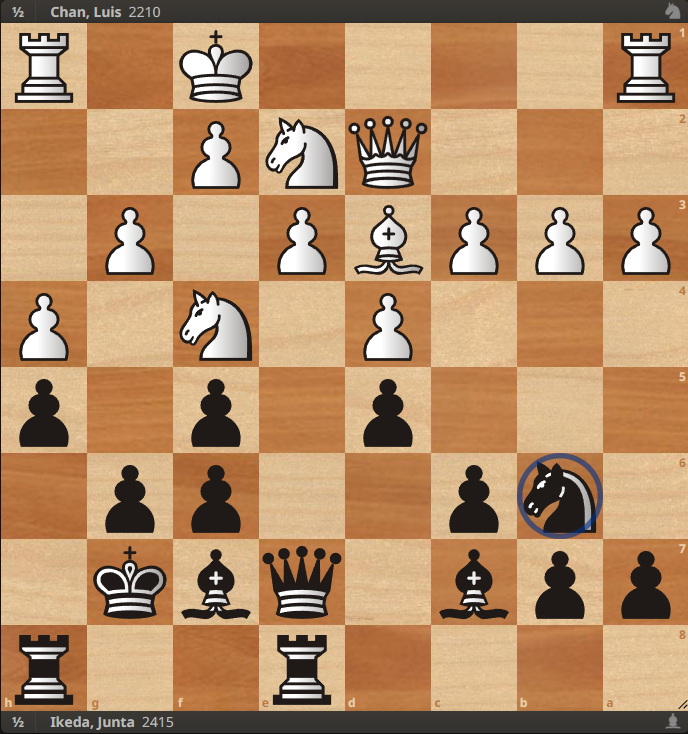

For example, in the position below as Black in a tournament game, I was thinking of how I could improve some pieces, and hit upon a good path for the knight. The game continued 18.a4 Nc8 19.Qc2 Nd6 20.Rd1 Ne4 and Black had a slight edge.

The game continued 18.a4 Nc8 19.Qc2 Nd6 20.Rd1 Ne4 and Black had a slight edge. Raymond adds that for most positions, you only need to calculate or look at plans that are a few moves deep to understand the position better.

Raymond adds that for most positions, you only need to calculate or look at plans that are a few moves deep to understand the position better.

I would add to his list, what kind of exchanges are possible and who they would benefit.

Of course, this depends on the type of position. If it’s a sharp, tactical position, it’s useful to calculate the most critical-looking lines on your opponent’s move to save time.

By thinking of plans and positional factors for both sides, you can use your opponent’s turn well without tiring yourself out. And when it’s your move, you’re in a better place to focus more on the details: calculating lines and evaluating them.

The next habit is a counterintuitive one.

Habit #3: Leave the board strategically.

Let me tell you a story. In 2018 I played a tournament in Serbia where a 12-year-old IM called Gukesh was also playing. Every round, he was fully focused at the board for the entire game. Even if it was 5 hours: same posture, same focus, no wandering off on the opponent’s move.

A few of us saw that and we were telling each other, “That kid’s going to be a monster.”

And 6 years later, he became World Champion.

The thing is, only a handful of chessplayers in the world have the ability to concentrate like Gukesh. Even the three grandmasters I talked to don’t stay at the board the whole game.

Tournament games take a lot of stamina, so getting up from the board and walking around has the benefits of de-stressing and letting your mind rest when it’s your opponent’s turn.

As Ian told me, when you return to the board, you can often view the position with fresh eyes and see new ideas. So it is important to conserve energy through the game by getting up, stretching your legs and taking a breather, also to destress.

But let’s be honest. Almost all of us can work harder on our opponent’s turn.

If it’s a critical position, you should be calculating. If it’s a quiet position, you should think of strong moves for the opponent and plans for both sides. With every game you play, you can train your focus and stamina this way on your opponent’s turn.

Here’s a rule you can follow: don’t leave the board until you’ve thought about one or two options your opponent might choose.

Once you realise how much scope there is to improve the way you use your opponent’s turn, you might be emulating Gukesh soon.

Habit #4: Think about plausible mistakes for both sides.

Australian GM and owner of the popular YouTube channel Molton, Moulthun, told me this is a habit of his. It’s a bit like blunder-checking not only for yourself, but for your opponent as well.

It might be a natural move they could play but gives you a tactic, or a way for you to get the advantage positionally.

For example, in the position below, Black has to move the attacked knight. While waiting for them to decide which square, you can calculate some of these yourself. I realised 17...Nbd7 looks natural, but it allows 18.g5 when the only square for the knight is h5, when White can capture and play Nh4, winning a pawn with a winning edge. And 17...Nbd7 happened in the game.

I realised 17...Nbd7 looks natural, but it allows 18.g5 when the only square for the knight is h5, when White can capture and play Nh4, winning a pawn with a winning edge. And 17...Nbd7 happened in the game.

By training this skill, you’re constantly on the lookout for tactical opportunities and you might spot a winning idea before your opponent plays their move.

The first tip was to look for the opponent’s strongest move. By also looking for plausible mistakes they could make, you’re training yourself to be flexible and curious.

- You won’t be surprised by as many moves because you’ve already evaluated some options as good or bad,

- You’re less likely to miss important variations, and

- You save time by putting your opponent’s turn to good use.

Moulthun also told me that when he’s playing someone he knows well, he’d try and guess their moves as a sort of game inside the game. That can help you concentrate or get into the zone because it’s pretty fun to predict your opponent’s moves correctly.

Habit #5: Imagine you or your opponent can play two moves in a row.

This might sound weird, so let me explain.

Firstly, on your opponent’s turn, you can think about what they’d do in this position if they could play two moves in a row. This can give you a hint on their plans or ideas.

Once you work out what they want to do, you can then get a better idea of

- how much time (or number of moves) you have to stop their ideas,

- how you can stop them, and

- whether you should do that or push on with your own plans.

Secondly, you can also think of what you’d play if it was your move again. That can give you a good idea of what plans you have and what the opponent can play here that would stop these plans.

Doing this, you can see how much urgency is in the position for both sides. The more urgent it is, the bigger the value of each move because wasting one move might decide whose attack gets through first or who can improve their bad pieces quicker.

On the other hand, if you or your opponent having two moves in a row doesn’t change much, it means there’s more time to improve your pieces or look for plans that take more time.

If you want a simple summary:

“If they have two moves, what would they do?” reveals their plan.

“If I had two moves, what would I do?” lets you see yours.

Compare these to help you see if the position is urgent or slow.

Recap

Here’s the checklist to run while your opponent’s thinking:

- their best move,

- how you might respond,

- plans for both sides,

- natural moves that are blunders, and

- plans when either side has two moves in a row.

The habits in this post have focused on classical OTB games, but you can apply the same thinking to online classical and rapid. In faster time controls like blitz, it’s still a good habit to think about your opponent’s strongest move and plausible mistakes for both sides, but you probably don’t want to get up and walk around.

Start on these habits in your next game, and let me know what you find.

If you’re not used to concentrating on your opponent’s turn, it’ll take a bit of time for you to turn them into habits. But I want to stress this important point:

Half of the time in every chess game you will ever play, depends on what you do when it’s your opponent’s turn.

So it’s really worth working on this if you want to improve your chess and fulfil your potential.

“Learning how to think" really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think.

It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience.

Because if you cannot or will not exercise this kind of choice in adult life, you will be totally hosed.”

―David Foster Wallace, This is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life

You may also like

IM datajunkie

IM datajunkieWhy your tactics aren’t improving

The 4 fixes that can help you become a tactician CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… thibault

thibaultHow I started building Lichess

I get this question sometimes. How did you decide to make a chess server? The truth is, I didn't. IM datajunkie

IM datajunkieThe 5 things I do before a tournament

Learnt from 25 consecutive years of OTB IM datajunkie

IM datajunkie25 lessons from 25 years of chess

Mistakes you can avoid and habits you can start with today GM Avetik_ChessMood

GM Avetik_ChessMood