Flickr: Gerlos

Why Are People Good At Chess?

The Rise and Fall of ChunksIntro

Adriaan de Groot

The Chunks

MAPP

CHREST/Templates

Misinformation

Adriaan de Groot Revisited

Criticism

Summary

Intro

E4e5nf3nc6bb5a6ba4nf6:

Chess players would have a greater memory for this sequence than non chess players as the letters can be represented by one opening (Ruy Lopez). This would reduce this string of numbers and letters to one chunk. Chunks consist of subparts which are grouped together.

A chunk is an element of memory.

In 1956, Miller published the famous paper: 'The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two'. The idea was that human short term memory capacity was limited to 7±2 items. He posited this because he looked at a bunch of studies like ability to make absolute judgements (estimating a degree) of sound pitch/loudness/taste etc.. And then he said that to do this without error required that the amount of distinguishing items to be in the 7±2 range.

He also introduced chunks by explaining how another study showed that binary number strings could be remembered through learning how to convert binary to decimal numbers. This means that a binary string such as 10100/01001/11001/110 could be remembered as 20/9/25/110 (left over). Miller referred to this process as 'recording'. You can see how this helps memory. Many cognitive scientists then looked at investigating the role of chunks in memory. They confirmed that it is indeed a real psychological construct that is used to aid memory recall.

Adriaan de Groot

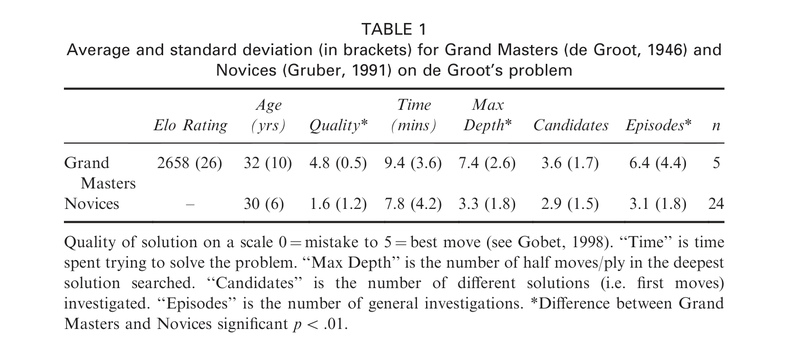

Adriaan de Groot was a psychologist and chess master who adapted their 1946 thesis into a famous book, Thought and Choice in Chess. The goal of his thesis was analyzing chess under the framework of Otto Selz who viewing thinking as a chain of linear processes. He analyzed the thought processes of Grandmasters vs Masters through giving them positions and having them explain their thought process out loud. He saw that there was little difference in the search statistics (calculation) of these players. That the amount of moves analyzed and the max depth did not differ. He also had the players reconstruct positions from memory and found that the Grandmasters could do this almost perfectly after looking at the position for only a few seconds. These findings were very influential on later chess research.

de Groot was an advocate of Selz's Denkpsychologie approach which used introspection to analyze processes of thought. This was in contrast to behaviorism which viewed internal processes as not suitable for study. Fernand Gobet commented on an interesting tension in how de Groot is viewed in chess literature. That the big mass of his work, the think aloud procedure and his analysis was placed in the background of later chess research. The research was more enamored with his quantitative findings (or maybe they couldn't be bothered to read his book all the way through because it was about 450 pages).

Adriaan de Groot https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Adrianus_Dingeman_de_Groot.jpg

Adriaan de Groot https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Adrianus_Dingeman_de_Groot.jpg

The Chunks

Herbert A. Simon (interdisciplinary scholar and artificial intelligence pioneer) and William G. Chase (psychology professor) had the ambitious idea of explaining chess skill through the chunking model.

William Chase (left) playing against Herbert Simon (right). Neil Charness (future William G. Chase Professor of Psychology at Florida State University) in background. https://zilsel.hypotheses.org/2319

William Chase (left) playing against Herbert Simon (right). Neil Charness (future William G. Chase Professor of Psychology at Florida State University) in background. https://zilsel.hypotheses.org/2319

Chunking theory for chess was developed by Chase and Simon in 1973 as a way to explain what makes a Master a Master. Chunking theory states that stronger chess players have a larger vocabulary of 'chunks'. 'Chunks' are groups of pieces that have relations between them (attack, defense, color, piece type, proximity). Stronger chess players would have more chunks stored in long-term memory. This would help them to remember the position as the perceived chunks in the current position would have already been encoded previously in their past experience. The labels of the chunks in the position would be held in short-term memory.

The amount of chunks held in short-term memory would be in the 7±2 range as given by Miller in his famous paper. The chunk labels would point to the content of the chunks which could then be retrieved (another study estimated that it took 2 seconds to recognize a chunk, and about 300ms to retrieve each subpart of the chunk). The chess chunks would implicitly suggest a move to play. Calculation was seen as simply verifying the initial move as opposed to being the driver of move selection.

They conducted a famous study in 1973, Perception in Chess:

Three players:

A Master (The master was inactive and had a lower performance compared to other active masters)

A Class A player (William Chase, one of the experimenters - seems biased to have the experimenter in their own study :O)

A Novice (Michelene Chi, a researcher in the field of expertise who later married William Chase, maybe they fell in love during the experiment XD).

Two Experiments:

There was an empty board in front of the participant where they would recreate the chess position they just saw. The positions were either real middle game or endgame positions (which were from real games) or were randomly created positions (pieces played randomly on board).

In the Perception experiment they recreated the board while being able to see the chess position on another chess board.

In the Memory experiment then recreated the board without being able to see it (the chess board with the position was hidden by a partition), so they had to recreate it from memory.

The experiment was recorded by tape and then the move times between each piece they placed was recorded. For the Perception experiment where they had access to the board they also recorded the times where the players glanced back at the chess position before placing more pieces on their board.

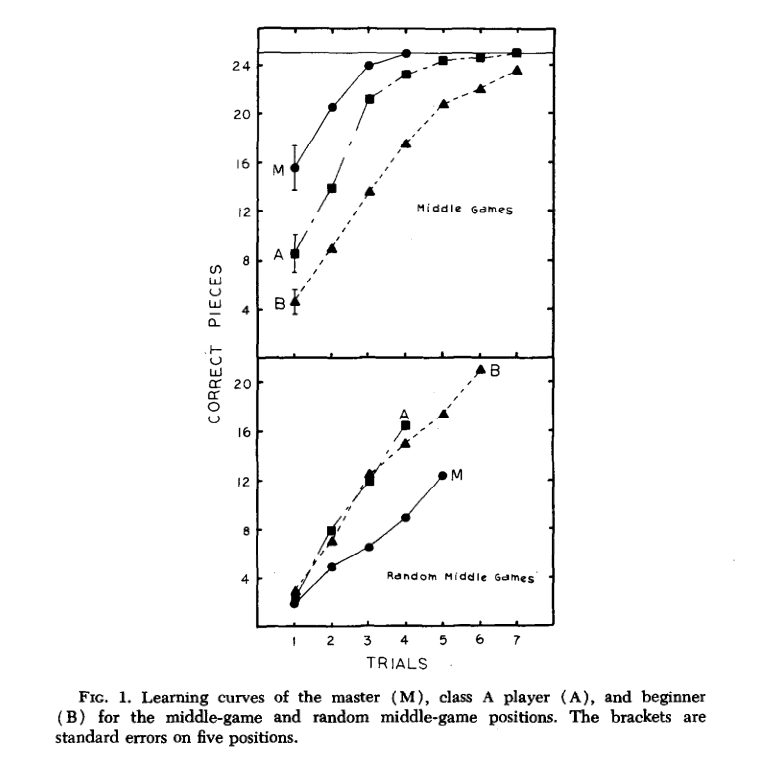

The stronger the player, the better they remembered the position. But for positions with randomly place pieces there was no pattern, the master didn't remember it more accurately that the lower rated participants. This seemed to suggest that chess memory was contextual and chess skill was based not of superior general memory but a more specialized kind of memory, only for realistic chess positions.

Memory for Real Middle Game Positions increases with skill (pattern was the same for Real Endgame Positions). But with Random Middle Games there is no connection with skill.

Memory for Real Middle Game Positions increases with skill (pattern was the same for Real Endgame Positions). But with Random Middle Games there is no connection with skill.

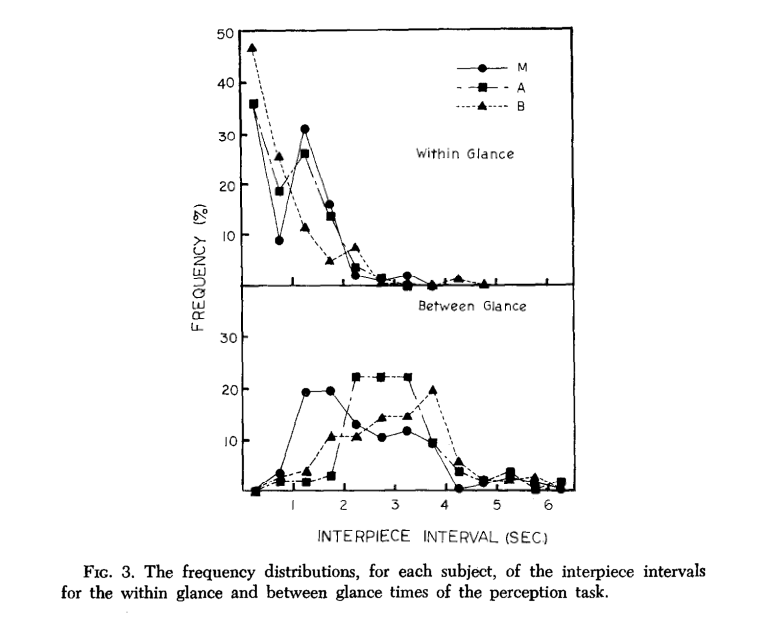

'Within Glance' means time spent between placing successive pieces (low times of .5 seconds were because players would pick up multiple pieces at once and place them on the board). 'Between Glace' means times spent looking back at the chess position in the Perception experiment, before recreating the pieces on their board.

'Within Glance' means time spent between placing successive pieces (low times of .5 seconds were because players would pick up multiple pieces at once and place them on the board). 'Between Glace' means times spent looking back at the chess position in the Perception experiment, before recreating the pieces on their board. The times between pieces placed had very similar distributions for the perception and memory experiments.

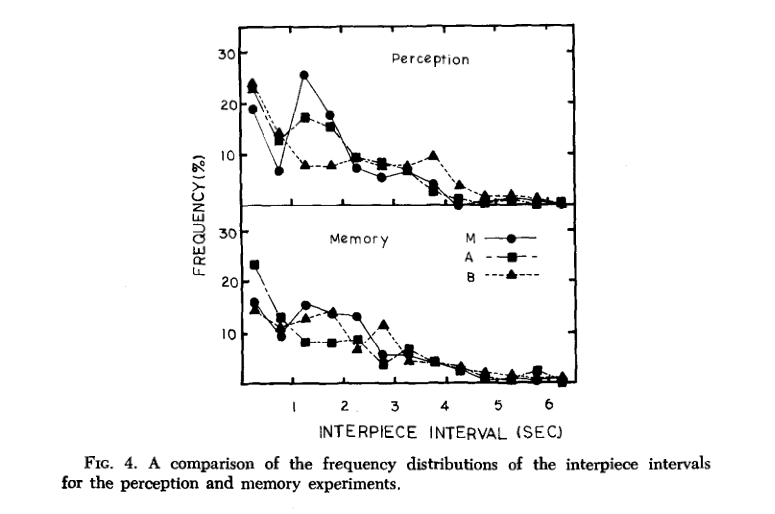

The times between pieces placed had very similar distributions for the perception and memory experiments.

Based on the data, they defined a chunk as a series of successively placed pieces, where the amount of time between each piece getting placed on the board was shorter than two seconds. They analyzed the relationship between chunk lengths and number of relations. They found that the shorter the time between successive pieces, the greater the amount of relations there were. This means that groups of pieces with greater amount of relations like attack, defense etc. were placed faster.

The time spent looking at the board in the Perception experiment between placing the pieces decreased with skill. The master didn't need to look as long.

Then they looked at the correlations for relations of pieces placed successively under 2 seconds (part of a chunk) vs over 2 seconds (not part of a chunk). There was a very high correlation (.89) for both the perception and memory experiments where comparing the relations of the chunks to each other. This meant that when looking at the board, vs remembering the position, the relations of the chunks were extremely similar.

However the correlation between chunks and non chunk piece relations were low. They also calculated the probabilities of relations if the pieces had been place randomly. There was no correlation between chunked pieces and the random pieces, However, the non-chunk pieces did correlate with each very strongly (.91), while also correlating very strongly with random piece distributions (.87 and .81) for the two experiments respectively.

Point is that the relations between pieces in chunks held were not random. And that their relations were strongly correlated both when the player was looking at the board vs taking it from memory. This indicated that chunks were indeed split into two second frames and that the players were using chunks to remember the board. On the other hand, piece placed with a span of over 2 seconds are not in chunks and the relations are random and not meaningful.

They estimated that 50,000 chunks were held in long term memory by a master. They pointed out an analogy between the chunks and learning words in a language, speaking of the chunks as a chess vocabulary.

MAPP

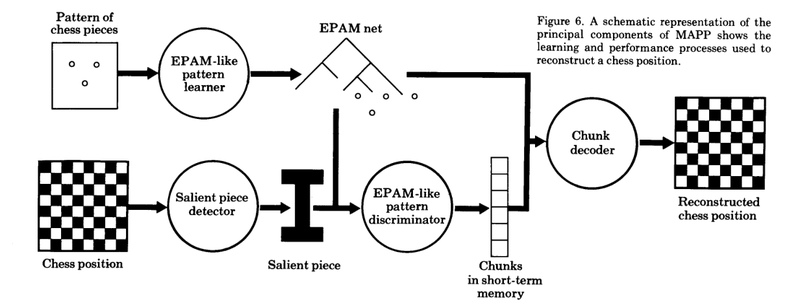

Chase and Simon discussed the MAPP program which combines the PERCIEVER program with EPAM (Elementary perceiver and memorizer) theory.

The PERCIEVER is the name of a program which emulates the way chess players look at a chess position in the very first seconds. It does this through scanning the board like a human, with a simulated fovea and a field of peripheral vision. It uses its peripheral vision to look for squares that attack/defense the current square and vice versa. Then it hops to those squares.

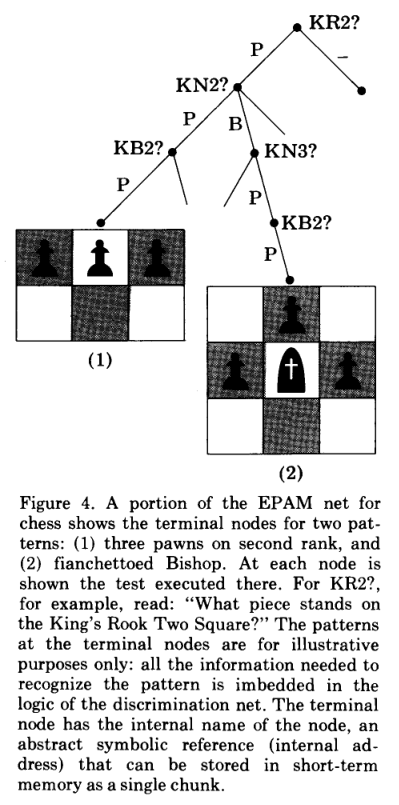

EPAM is an earlier model of human memory developed in 1964 by Simon and Feigenbaum. It was adapted for chess in 1973 by Simon and Glimartin.

EPAM holds chunks in a discrimination net. A chunk would be detected through queries. If an element is found to be in the stimulus then that query is positive. You go down to the branch at at the end is the chunk.

Diagram of MAPP. Learning at the top, Perception on the bottom.

They also referred to their experiment and noted that the Master had on average a larger chunk size than the Class A player (3.8 vs 2.6 pieces). However, their theory predicted that the Master would have more pieces in their chunks. Also, since short-term memory was supposed to be constant, the different in the average amount of chunks per position was also not predicted (7.7 vs 5.7 chunks). They concluded "At the moment, we have no good explanation for the discrepancy, but have simply placed it as an item high on the research agenda."

Now for the question of how chunks translate into moves. Apparently a 'pattern' suggests a move in itself (the term chunk metamorphosed into pattern for this last part of the paper). A 'production' would consist of a condition part (test whether a perceptual feature is present), and an action part 'move the rook to the open file etc'. Then there would be a tree search. This explanation was tucked at the end of paper and not elaborated on too much.

The role of perceptual processing in chess skill seemed to balloon in importance between their papers in January 1973 and July 1973:

One key to understanding chess mastery, then, seems to lie in the immediate perceptual processing,

Thus, we suggest that the key to understanding chess skill—and the solution to our riddle—lies in understanding these perceptual processes.

CHREST/Templates

Fernand Gobet. http://chrest.info/fg/home.htm

Fernand Gobet. http://chrest.info/fg/home.htm

Chunking theory still had questions to answer. Memory performance for two simultaneous boards did not diminish as expected according to chunking theory, they were remembered almost as well as one board. Also when presented with multiple boards successively, memory also didn't diminish as expected. If short-term memory of chunks explained performance completely, then memory should've deteriorated rapidly in those experiments as there is only a 7±2 memory span for the chunks.

These observations motivated the development of the CHREST (Chunk Hierarchy and REtrieval STructures) program in the 90s by Fernand Gobet. You can consider it a Neo-Chunking model. CHREST was based on the EPAM model. Gobet also introduced the idea of Templates. Templates were basically bigger chunks, an example is the Ruy Lopez opening pawn structure with piece in typical positions (Bc2,Nf3,Ng3 etc). Templates would be formed when some chunks would occur very frequently with each other. This would explain why multiple boards could be remembered, as templates would be stored in long-term memory. Templates could also link to other templates and also had pointers to semantic information. In the chunking tradition, Gobet emphasized pattern recognition over search.

Gobet also collaborated with Herbert Simon, one of the original creators of the Chunking theory. Gobet and Simon replicated the original 1973 experiment with computers where people could drag the pieces on the screen. It turned out that the mean of the median largest chunks was 16.8 in the recall task for the masters. The median largest chunk for the master in the original recall experiment was 5 pieces. This is a big difference. It turned out that this might have been because physically placing pieces in the original experiment artificially limited the amount of pieces per chunk, as physically placing pieces took more time. Also template theory would predict a larger chunk size anyways.

When the CHREST program predicted that masters would actually have a better performance on random positions compared to novices, Simon thought that it must be a mistake. They then performed a meta-analysis combining all studies which had looked at memory performance for random positions. They found that experts actually had a slightly better performance on randomly generated positions than amateurs, despite the original study saying no difference (also the original study was the only study were the wasn't a difference). The stronger random performance was explained as stronger players could look for remembered chunks within the randomness. The chunks may sometimes appear coincidentally in random positions.

Gobet also wrote a book with Adriaan de Groot called Perception and memory in chess.

Misinformation

Misinformation: The chess/expertise literature ended up getting confused over the details. It was commonly claimed that De Groot found no difference in search (calculation) performance between Grandmasters and Amateurs. These claims were false of course because De Groot was comparing Grandmasters and Masters, not GMs with amateurs. The no difference in performance became dogma.

There are major differences in search statistics between Grandmasters and Novices.

Adriaan de Groot Revisited

This was one of the positions shown to the masters and Grandmasters in De Groot's study. Max Euwe, a former World Champion was shown this position and asked to think aloud their thoughts starting after 10 seconds of looking at the position.

Black is down two points of material. Also White has a queenside pawn mass which could advance. But Black does have the bishop pair which "can often perform miracles" as Euwe said. Euwe also said the position should be handled actively as "If you wait and see, you will probably lose against all those pawns."

What is notable is the conceptual understanding here, the knowledge of how the bishop pair can be tricky and the dangerous future potential of the White pawns. This leads to a feeling of needing to get active now, to get the rook into the game and starting harassing the king.

de Groot proposed four phases of chess reasoning: Orientation (immediate consideration of the position), Exploration (searching different lines), Investigation (choosing the move to play through narrowing the lines looked at and going deeper down those lines), Validation (checking the chosen line works).

Criticism

The idea that chunks are the most prominent facet of chess understanding has been criticized by other researchers in the field of chess reasoning.

--It was emphasized by chunkers that chess players' strength does not deteriorate markedly when thinking time is decreased. But this was an assumption that was not tested. Chabris and Heart found that thinking time does improve chess move quality 'substantially'. They also criticized Gobet, saying that he underplayed how blunders increase dramatically when having less time to think, sarcastically adding "Like Gobet, we are both chess masters, and we are sure that we would all like to see our opponents make mistakes that large."

--Players also align their thinking times to the benefit of thinking and that stronger players have a greater ability to do this. This is the opposite of what we would expect if chess chunks simply 'suggested a move' immediately. If calculation is simply a matter of verifying an initial move, then why do people think more, when thinking more is objectively a good idea?

--Lane and Chang conducted a study analyzing the factors of chess memory. They performed a hierarchical regression analysis to predict chess memory with these variables: chess related experience (studying alone, tournament games and non-tournament games), chess knowledge and fluid intelligence.

--They found that even when controlling for chess experience, chess knowledge explained 13 percent of the variance in memory and that fluid intelligence explained an additional 16 percent. This is not explained by chunking theory, as experience can be seen as measuring the amount of chunks they would learn through experience.

--Lane and Chang also ran another study to look at chess skill this time. The performed another hierarchical regression analysis with the variables as chess related experience (studying alone, tournament games and non-tournament games), Domain-General Fluid Intelligence, Chess-Specific Fluid Intelligence and Chess-Specific Crystallized Intelligence. They found that these intelligence related factors did contribute meaningfully to chess skill.

--Psychologist Anders Ericsson had famously proposed that expertise in general was a function of deliberate practice. That deliberate practice was the main driver of skill. Learning chunks is compatible with this idea (it would still need to proven though). Learning chunks would simply come with deliberate practice. However, experience only accounted for 60% of chess skill under the most favorable analysis in Lane and Chang's study. If expertise was the single big explanation than where does the other 40% of chess skill come from?

--Linhares et al. looked at elements which separated chess memory performance for different skill levels. They found that sometimes a amateur could remember a pawn chain better than a master. The masters focused on salient conceptual ideas in the position and they would occasionally forget this kind of detail. But chunking theory would suggest otherwise.

--Chabris had chess players look at famous chess positions. However, they would alter the positions so that there would either be one 'relevant' change, 1 irrelevant change or 2 'irrelevant' changes. Relevant means it would alter the meaning of the position fundamentally. A change was done to only one piece in the meaning condition to keep the change constant. The participant were then given the positions and then were shown a changed version of one the famous positions. They then had to give their confidence level that the position was the same.

--For both the one and two irrelevant change conditions, the confidence level was equal (59%). Furthermore, the relevant change condition dropped the confidence from 71% to 40%. The chunking theory would predict a difference for an extra irrelevant change, but it stayed the same. Also the meaning changed dropped the confidence way further than just an irrelevant change. This shows that conceptual understanding is not accounted for in chunking theory. (Keep in mind, the meaning change is quantitatively the same as one irrelevant change as it is only one piece that is changed).

Summary

There are number of things not explained by chunking theory:

- How does a chunk/template suggest a move?

- Since there are many chunks, which chunk suggestion should be chosen?

- Why does confidence for chess position equivalence not align with what chunks would predict?

- Why do people's thinking times align more closely to the benefit of thinking as chess skill increases?

- Why does thinking time improve move quality even though search is supposed to be simply confirming the move you initially thought of?

- Why do different types of intelligence help chess skill and chess memory?

- Where do abstract conceptual considerations come from?

What chunking theory does is forcefully impose proven cognitive processes for memory onto an explanation of chess skill. It's like trying to fit a circle into a square hole. Remembering chess positions, and finding a move are fundamentally different processes. That chess memory and chess skill correlate with each other does not mean that they have the same explanation.

The way memory is organized for a chess position when trying to recall it, says nothing about how the ability to find good moves develops. Chunks/Templates may well explain how a position is recalled. But this doesn't means that chess skill predominantly involves chunks/templates. And how could conceptual understanding, abstract patterns, and search etc. be shown in memory experiments? The answer is that they can't. So using memory experiments to make authoritative conclusions on how chess skill develops is unjustifiably limiting.

Finding a move does not require remembering every detail on the board. The two processes are qualitatively different. For elements which chunk/templates may suggest (assuming that they can suggest moves in themselves), there has to be a way of putting it all together. This would obviously involve search to combine them. But how would chunks/templates suggest moves? If there are about 7 chunks which suggest a move, how do you know which one to choose? Search statistic shows that players do not look at 7 different moves, but only about 2-3 candidate moves. If chunks/templates can suggest multiple things, then there is still the question of how one move is chosen. Giving calculation as the answer to this question doesn't explain it because the way the chunks/templates inform each move of search lines has not been defined at all. The role of search has been completely dismissed by chunkers with no research into how search is informed by chunks and templates.

Templates were a way of trying to save the chunks. The problem with templates in explaining chess skill is that it has been researched in the context of chess memory only. There has not been an reasonable explanation of how templates/chunks can lead to the selection of a move. Looking at Euwe's analysis in the De Groot protocol shows a definite evolution of thought, first a kingside attack, then a consideration of a blockade against the pawns, and then back to a kingside attack. There's also abstract conceptual ideas like bishops "can often perform miracles".

De Groot noted that a master's thought process shows progressive deepening, going back and forth between lines in a free fashion, and expanding previously looked at lines in the process. Information from the different lines can help influence ideas. Strong players have the ability to explain positions in a conceptual way to help other understand the 'essence' of the position. But this essence would require a synthesis from different considerations which is the function of search and calculation.

Overall Chunking Theory is a simplistic and unrealistic way of explaining chess skill. It was used when analyzing recall of positions. Since masters were better at chess and they were also better at remembering positions from real games, the logic was that chunks are the answer to their ability at chess. But just cause two things are correlated, doesn't mean they have the same cause.

Chunking is a demonstrated phenomenon when it comes to remembering simpler things like word or number lists. However, this has not been shown to transfer over to explaining chess skill which is much more nuanced.

And this classic study is an example of how some papers are overhyped and how some views can take a vice grip.

It's like a filter where you can only see things one way as a result.

You may also like

RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000The King Walk

Master the Art of the King Walk RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000AI Slop is Invading the Chess World

Claiming that AI can teach chess is the latest fad SayChessClassical

SayChessClassicalAre Online Chess Players Trapped Pigeons?

The Increasing Gamification of Online Chess thibault

thibaultHow I started building Lichess

I get this question sometimes. How did you decide to make a chess server? The truth is, I didn't. Davis2010

Davis2010Music from Chess Moves

Hey, you may have used the pentatonic sound mode on Lichess. We're going to recreate some songs usin… RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000